Sabaritha Urnavur

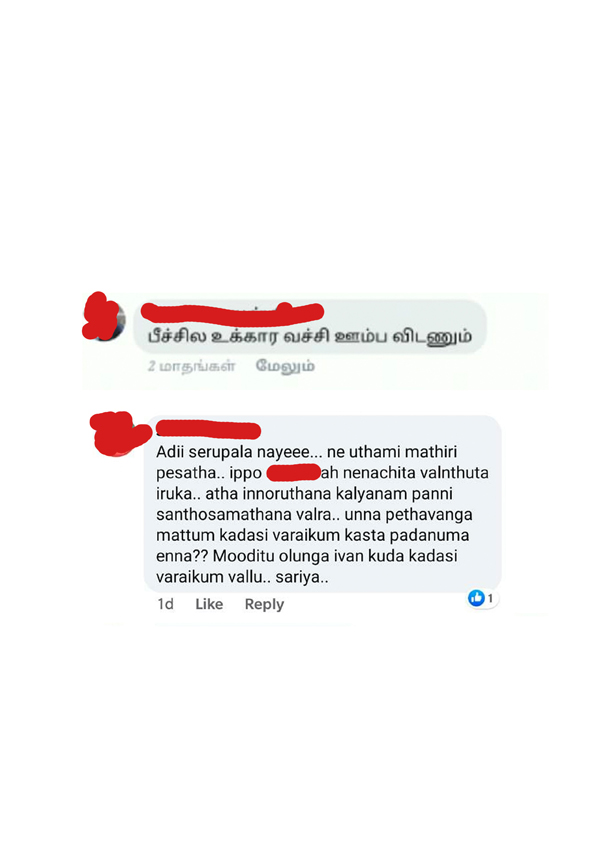

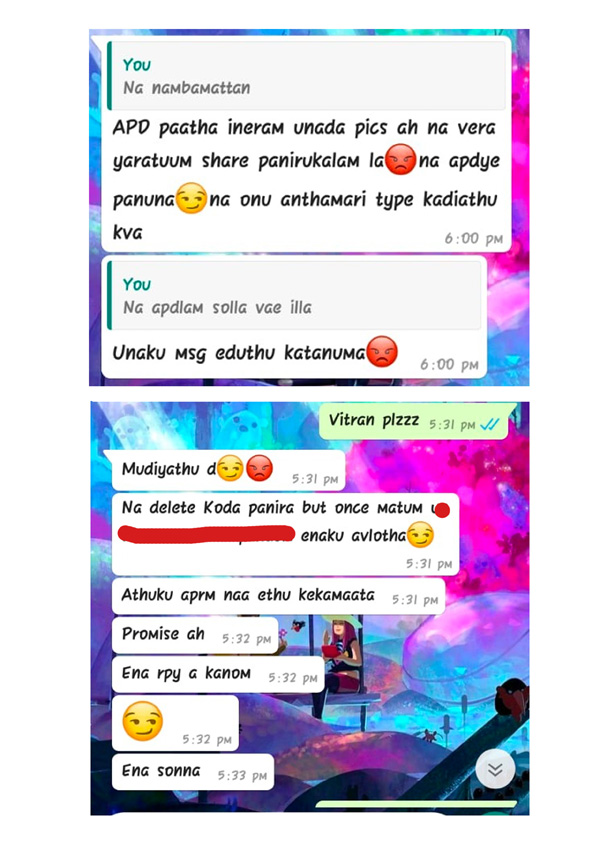

Dirty words are very potent weapons. Once lodged inside, they fester, undermining confidence, self-respect, sense of security and self-worth. Once limited to face to face abuse, now they reach the remotest corners of the world through omnipresent media. The internet is the host which spreads this vile disease at the speed of light. Those who are targeted, mostly women, find it difficult to categorise it as abuse, harassment. Those to whom she complains, asks for support, many times are unable to judge the enormous amount of damage their ugly sharp abusive words do. Going through the harrowing experience of cyber sexual abuse, Sabaritha Urnavur, a photojournalist and social worker from Chennai, Tamilnadu, India, inquired about similar experiences of the women in her contact. She found this to be too common and widespread at the same time either ignored or hidden within, not shared with others.

Over the years she talked with a lot of women and tried to understand this abusive behaviour on the internet. From this emerged her photo essay titled ‘Infected Net’. A series of photographs showcase very succinctly and effectively the plight of women, on the net, through the net. This was seen and appreciated by a large audience for its content and a very important, most needed message.

At the tender age of 15 years, she remembers receiving the ‘message’, “Fuck you”, the meaning of which she was totally unaware of. One of the girls known to her was blackmailed by her ‘boy friend’ using the photographs and screenshots of the messages to use her sexually without her consent. As a result she committed suicide. Sabritha’s advice to such victims was not to feel low but trust oneself, and believe that you have not lost anything.

Her mother committed suicide when Sabritha was only 4 years old, which was obviously, severely traumatic to her. She herself was threatened, blackmailed by her ex-boyfriend using her images and creating fake identities in her name. She learned that she is not alone, every woman around her was being abused. This abuse in any form leaves a permanent deep impression on personal and professional life. She underlines that our society, instead of understanding the plight of the victim, behaves as a misguided moral police and instead of the abuser, the victim is labelled as guilty. As she found the abuse almost omnipresent, she plans to widen her field of work geographically and empathise with the victims by documenting their sufferings and struggles.

Now she wants to expand her sphere of work across India, by communicating with many more women. Listening to women across India, documenting harassment, abusive content in social media and communication platforms, compiling that with the complaint to cyber cell. Documenting case studies from the stories including images, in order to document emotional, social, economic, political impact due to cyber abuse and violence. To document the fight and how the victim manages to overcome the trauma. The project “Self -portrait” portrays the emotions of women affected by cyberspace violence. Expected Outcome of the continued extension of the project, under the grant from Photography Promotion Trust, is to sensitize and create discussion on impact of cyber violence occurred to women. To improve the standards of community guidelines & cyber protection and safety in India.

About herself she says,

“I was born in town and brought-up in the city. My observation on cyberspace violence occurring to rural women is that there is access to cell phone and internet everyone. Due to (patriarchal) family structure and lack of confidence to face any issues. Women feel that they will lose dignity if the village people know about the abuse since most of them are relatives.”

When questioned, “In your opinion why is the abuse around us ignored?”

She said that, “Vulnerable people are easily abused due to the patriarchy structure. Abusers are also victims because of ignorance and power influence. When it comes to cyber abuse, People are not even recognizing it as abuse. Their main aim is to control the voice of the vulnerable.”

Q. “Why do men behave like this? Insecurity, lack of self-worth, to prove their superiority? Any other reason?”

A. “Being men is not a problem but being male chauvinistic is dangerous. The men’s world is preparing our children for an inequality society. Our School, media, family everything are male centric.”

Q. How to change this?

A. Legal cover and Strong policies for cyberspace violence and digital literacy from the school itself will make some changes

Q. How to unite women?

A. Periyar Says that “Women in India experience much worse suffering, humiliation and slavery in all spheres than even untouchables” so in my understanding bringing the women out of slavery will help us to get united.

Q. What will be the role of mothers in this in nurturing the male child?

A. Role of the mother itself is gender stigmatized. There is also a father role in bringing up the child. Children learn and inspire from the father then cartoon characters, local big brothers, and heroes in the movie. Firstly, parents should act with gender equality in front of children. Then the parents should avoid gender discriminated cultural practices, jokes, advice and so many family things while bringing up the child.

She expects that the project will sensitize and create discussion on impact of cyber violence on women who are the targets and victims of this abuse. She expects to work towards improving the standards of community guidelines and cyber protection improving the safety of women in India.

She continues, “I still don’t understand men! They said if you show a woman part by part, it’s not vulgar… They asked me whether I’m coming from a (good) family or not. These are professional photographers, assistant directors…men who read literature! While one asked me to share the images again because he’d not seen it ‘properly’, another told me not to post the pictures anywhere,” she says. The reception from women was markedly different. “None of the women questioned me. Even the ones who are not particularly ideologically inclined,” she adds.

Though recognised as a crime, many women are expected to put up with online harassment because it’s not taken as seriously.

Sabaritha is determined to live an independent life, and stays alone in Chennai. A graduate from the Madras School of Social Work, Sabaritha has been working with non-governmental organisations for the last 4.5 years. She uses the camera as a form of self-expression. “Last year, I wanted to practise photography but I wasn’t interested in doing it around a theme. I was alone and I only had my phone to connect to others. I found that the messages, good or bad, I received from people I knew had a great innocence on me. I literally felt suppressed at one point. Someone I know suggested that I write about it but I didn’t know how to convey my thoughts in words. I had a camera and a tripod and I decided to capture my emotions… whether I was crying, getting angry or acting crazy,” she recalls. For this project, which happened prior to Infected Net, Sabaritha placed the pictures along with the messages that elicited the response. Infected Net too is along similar lines, and began from conversations that Sabaritha had with women around her. She spoke to around 20-25 women about their experiences.

“I asked them what kind of messages they received, how they responded to it. At some point, it occurred to me that I should document this. For 8-9 months, I spoke to women expressly with the idea of documenting their experiences online. Even senior journalists have gone through cyber violence,” she says. Sabaritha recalls that when she was 15, she received obscene messages from a boy her age. “I wondered why someone would use technology this way and send such comments. Do they not regret it at all? People don’t even accept that leering is abusive, so they don’t get why such messages are abusive. They ask why you can’t just ignore it. They say don’t post photos. Why don’t they recognise it as abuse?” she asks.

Sabaritha points out that such messages leave an impact on the recipients and that’s what she wished to portray through the project. One of the screenshots is a threat to leak nude images of a woman. “My advice to her was that it’s just a photograph of her body and she must not feel guilty or ashamed about it. I told her that if the man leaks it, we can make a complaint but she must not be silenced or hide herself because of it,” says Sabaritha. She adds that along the lines of Sexual Harassment of Women at Workplace (Prevention, Prohibition and Redressal) Act and Internal Committee (IC) for sexual harassment complaints at workplaces, community guidelines on social media

Though many women spoke to her about the abusive messages that they had received, Sabaritha says that most of them had deleted the messages because they had been so disturbed. Most of these messages come from random strangers online and fake IDs; but sometimes, there are known men too who behave this way, Sabaritha says. “A senior, well-known photographer I know asked me if I wanted to sleep with him. He has a family. I have screenshots as evidence. I put up a general post about this, without naming him and within two days, he messaged and told me that he’d ‘realised’ his mistake,” she says.

Although many men do not respect a woman’s right to consent and feel entitled to comment on her body, a woman being comfortable in her own skin is something a lot of them cannot digest. When Sabaritha shared her photographs, in which she appears in the nude, she says that the women were appreciative while the men had moral lessons to offer.

Written & Transcripted by Anirudha Cheoolkar