Aug. 2020 Vol 01 | Issue 01

“I imagined myself to be a

manual scavenger”

M. Palanikumar interview by Shraddha Ghatge

Translation by Maharajan Thevar

Equipped only with a tiny GoPro, a 28-year-old M Palanikumar dived right into the waters of -a fishing hamlet in Tamil Nadu to capture the working lives of seaweed harvesters who earn their living by collecting the seaweed and algae. He bobbed along with them, followed their story, and emerged from the waters with some breathtaking photographs and a story which bagged an award for the Best Story by the Public Council of India earlier this year.

Whether documenting the inhuman practice of manual scavenging, capturing the haunting eyes of the children of manual scavengers in monochromes in exhibition titled ‘I too am a child’ or clicking the working lives of socially invisible community of seaweed harvesters and fisherwomen, Palanikumar’s photographs evoke nothing but mind-numbing desolution of the marginalised communities.

Palanikumar, one of the cinematographers of Kakkoos (meaning “toilet” in Tamil; it’s a documentary on manual scavengers in Tamil Nadu by filmmaker Divya Bharathi), talks to Samyak Drishti about his journey from getting his photos displayed in various exhibitions, armouring children of manual scavengers with cameras, teaching them photography, hosting exhibitions for them, and winning awards.

Tell us about your journey so far

Once I completed my engineering, I was keen on working, but not in a nine-to-five job. I soon joined an organisation named Clay fingers 7 which travelled to tribal areas across Tamil Nadu educating children in arts and crafts. I taught the children basics of photography like how to hold a camera and click photos. It was the travels with this group which made me pick up the camera seriously and learn the ropes of photography by myself. I was so fascinated with the camera that I even took it with me to bed. I realised I had found my calling. With my parents being fisherfolk, we barely managed to make ends meet. I had to take a loan to buy my own camera, which I did, and thus began my journey.

Through Clay Fingers 7, I was able to connect with Tamil filmmaker and activist Divya Bharathi and began working as one of the cinematographers with her on a documentary titled ‘Kakoos’ highlighting the plight of manual scavengers. Working on this documentary exposed me to the horrendous life of manual scavengers and how the practice affects their family, especially children. I realised how most of the children have to inherit this occupation due to the caste they are born into. That’s when I realised and decided to do something, to break this cycle of inheritance, by making use of photography. Thus, I began learning the craft by myself, clicking photos and hosting exhibitions for these children. This is how my inseparable journey with the lens began.

Meanwhile, I became a part of the Photographers for Environment and Peace Collective (pepcollective) a volunteer collective of photographers and film makers and have also been a 2019 Fellow with People’s Archive of Rural India (PARI).

What are your thoughts on manual scavenging and the issues of marginalised communities? What goes through your mind when you click their images?

This practice of manual scavenging is a result of systemic oppression happening since generations. It’s a punishing job! Most of the men diving into the dark sewers are in an inebriated state so that the foul stench emanating from it becomes a bit more tolerable.

It’s difficult and outrageous to watch them descend into the sewers or unclog the toilets or clean open drains with their bare hands, but the discrimination against them is so internalised that they themselves have accepted this work as their fate and carry on with their lives.

Even in schools, the children hailing from these communities are sometimes asked to clean the toilets. Their children face prejudiced comments when they graduate and try to seek alternate options for jobs. Only some students have been able to successfully seek an alternative career. Their life has not particularly improved, however, the previous generation wants their children to move out of this rut and so do the children.

While working on Kakkoos, all I tried was to put myself in their shoes, imagining if I were a manual scavenger myself. It was very painful.

Walk us through your process – your inspirations and motivations

I had no formal training in photography. It was the children of manual scavengers and their innocence which motivated me to work on these projects. I remember, in one of the exhibitions I had hosted for these children, a girl walked up to me saying that her parents had warned her against interacting with the children from the manual scavenging community, but when she saw the photos, she realised their suffering and felt sad about the reality. It was surely not her fault to think that way, she was raised with certain notions. However, these are the moments which keep me going.

I also draw inspiration from the works of Padma Shri Sudharak Olwe who has worked on this issue quite extensively. His words “Keep working and never stop” – have always stayed with me. Photographers from the pepcollective – Amirtharaj Stephen and Sarva Prakash – also teach and support me. In my earlier days, I attended a workshop conducted by National Geographic, it was because of Stephen I received this kind of exposure. Ever since, I took photography seriously. I have also been inspired hugely by my mentor Ezhilarasan (Founder of Clay Fingers 7), photographers Steve Rodricks and Arun Vijay Madhavan who helped me in every step of my initial journey and wording my stories.

How did you come up with the award-winning story of seaweed harvesters of Tamil Nadu?

A friend of mine suggested this idea to me. I did this story in 2019 during my fellowship with PARI. After a tedious process of seeking permission from labour department and with no plans, I simply dived into the sea with seaweed harvesters taking a GoPro along with me. It was my first time in a boat. It was so enlightening to know about their lives. It was easier to relate to them as my parents are fisherfolk. A woman, who has been working as a seaweed harvester for her entire life, said to me that they have been more on sea than on land, that the sea is very important for them. I also learnt about several fishing communities in the Gulf of Mannar. It went on to receive the Best Story of the Year (2020) award hosted by the Public Relations Council of India.

You host exhibitions from the children, tell us more about it.

I started with no support. I had to borrow cameras from my friends and invest my own money for the workshops and exhibitions. It was difficult, but it was only because of the support I received from veteran journalist P Sainath and his organisation – (PARI) and pepcollective that we were able to expand these workshops. P Sainath and PARI have been kind enough to provide support to me for my workshops and stories. So much so that we selected a few children from each district and handed over cameras to them. The intent is to empower them; to make them shoot their own parents while working; to make them tell their own story.

As an independent photojournalist, how do you supplement your income, especially during this COVID-19 pandemic?

This COVID-19 pandemic has badly hit all my projects. For now, it’s a struggle to make both the ends meet. I sell fish with my mother for a living and I have also been making a film about it. I never had a television in my home, so with increasing projects, I had bought a TV on installment. However, due to this pandemic, I’m finding it difficult to pay the installments. But even in these hardships, Sudharak sir’s motivational words keep ringing in my ears, and I continue to shoot photos of manual scavengers. PARI also helps me apply for other grants. My family and I have been surviving on the financial help provided by PARI and others who have been kind to me and have always supported me throughout.

Share your experience as a PARI Fellow. What have you learnt in the fellowship?

It was senior journalist Kavitha Muralidharan who helped me get this fellowship. PARI has helped me tremendously to hone my skills. I learnt how to identify and develop a story through their workshops. I never noted names of the people I clicked. PARI has always been strict with details and information gathering. They taught me to do a thorough prior research and narrate the story through the eyes of the person. I would carry these lessons with me for the rest of my life. Besides, Kavitha Muralidharan has been a crucial person in translating all of my stories. I have a ton of stories to share and my learning curve has only begun.

You received one of the Top Ten Humans 2019, Vikatan Awards and Best Story of the Year 2019, Public Council of India, Award. What do you and your family feel about your awards and achievements despite all the odds?

My family was naturally very happy that I received these awards. My father was elated, too, but says that it’s good that my son is getting awards, but not salary.

What has photography taught you? Are there any tips or tricks for the aspiring photographers and artists?

In the numerous exhibitions and stories that I have done so far, I have learnt that the most important thing is to earn the trust of the people one is working on. And this can be achieved by doing what they are doing. For instance, my recent photo story was on sugarcane cutters. I myself tried to cut the sugarcane to relate to their experience. Besides, photography is hard work. It’s not just clicking photos and getting over with. One needs to be smart enough to understand the technical aspects and later stages of the editing and printing of the photos.

I work on only those stories where I can revisit those people and follow their lives for a long time. It is no one-time thing for me. Photography is powerful enough to bring about a social change or reform. For instance, my 17 photos were published in Caravan magazine. I had followed and documented the lives of seven families of manual scavengers. After the story got published, they began receiving financial help. This kind of a change means a lot to me.

My aim is to evoke empathy in the minds of people towards the marginalised communities so that it brings about some long-lasting change in eliminating discrimination.

Manual Scavengers

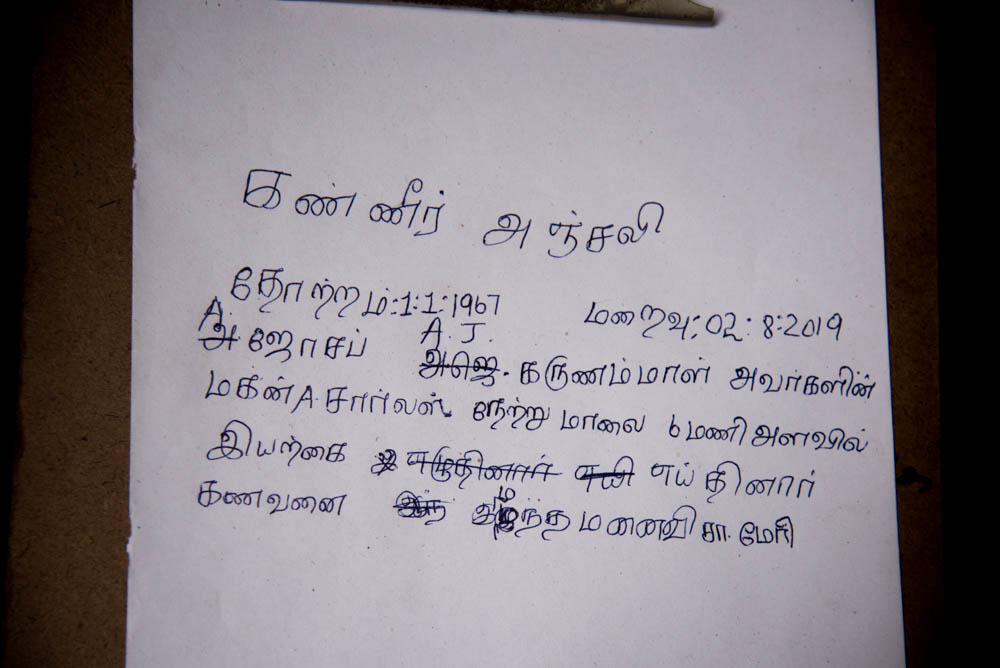

Relatives receive dead bodies of Murugan and Pandidurai at Coimbatore government hospital’s mortuary.

Iyyamma, 20, wife of Murugan outside Coimbatore government hospital mortuary waiting for her husband’s dead body. He was killed during manual scavenging.

Public toilet’s sanitation level is maintained below safe human standards across India. Manual scavengers would have to use their bare hands to unblock these toilets.

Manual scavening workers are not given proper equipments. They are often left with plastic bags to wrap around while cleaning human waste in sewers.

Many suffer from various skin diseases after prolonged exposure to human waste and other dangerous wastage that they have to deal with bare hands and no proper health and safety measures.

Baby shower function happening just a month after her husband’s death. He was killed when he went down the manhole.

Two manual scavengers dead at Madurai.

During the corona outbreak across the globe in recent weeks, Chennai city has been put under complete lockdown. Shutting off its borders, shops, malls and putting people in their homes. Manual scavengers has been tediously working through these days fumigating and sanitising the city for the well being of its citizens.

Seaweed Workers

Shraddha Ghatge

Member, Editorial TeamShraddha Ghatge is Mumbai-based independent journalist covering social, health, and civic issues. She has written for Firstpost, Newslaundry, People’s Archive of Rural India, Deccan Chronicle and Zeit.de. She has also worked with Mumbai Mirror, Firstpost, and on research projects with Tata Institute of Social Sciences, Mumbai. She has been a content writer for photo documentation on social issues in collaboration with well-known photojournalist Sudharak Olwe.