When I was asked to write about a film, analyze it frame-by-frame, I was confused about what to write, which movie to pick. It’s mainly due to the 100-year-old history of Indian cinema and having been lived as a student of cinema and early career practitioner.

In an age of virtual reality and easy accessibility, watching movies on several streaming platforms and mobile phones has become the new normal. When one is spoilt for choices, which movie should one consider worth watching to learn becomes a difficult decision. As the German Philosopher Friedrich Engels once said, “Everything must justify its existence before the judgment seat of reason, or give up existence.” Similarly, my attempt here is to justify the absolute necessity of going back to classics; to understand the past, which helps us shape the future. I’m not even considering the ‘present’ because we don’t really know what will come of it.

For the ones who haven’t seen it, the first all-time classic movie for this issue has to be the Bengali film ‘Charulata’(also known in English as ‘The Lonely Wife’) directed by Satyajit Ray in 1964. Of course, some of you must have seen it, but my intent is to stoke your interest in studying this movie through a filmmaker’s lens. I don’t claim to be an expert in imagemaking but as a filmmaker and an occasional photographer, I would take time to dwell upon certain contradictions between the cinema image and photography, how both can help and even disturb each other. I’ll try to keep this essay as scientific as possible, however, should you see any glimpses of me romanticizing the movie, that would be because of my love and admiration for Madhabi Mukherjee (the lead actress), Satyajit Ray (the filmmaker) or Subrata Mitra (the cinematographer).

Another reason to choose this film is because of its timelessness. There have been direct remakes, influences, and even cheap rip offs of Ray’s Charulata in so many films. Even the recent film (released on a streaming platform), ‘Bulbbul’, reminded me of Charulata, but I haven’t heard the director speak about her influences.

Direction – Satyajit Ray.

Screenplay – Satyajit Ray, based on ‘Nastanirh (Broken Nest)’ by Rabindranath Tagore.

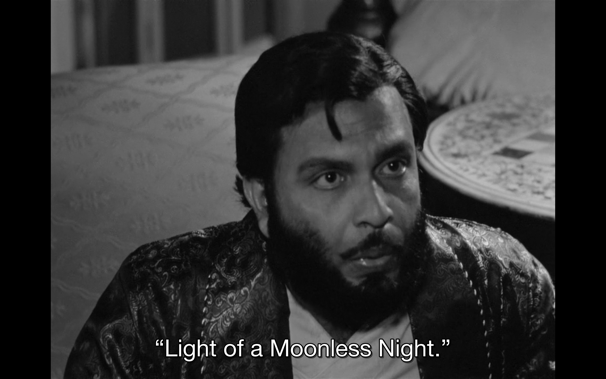

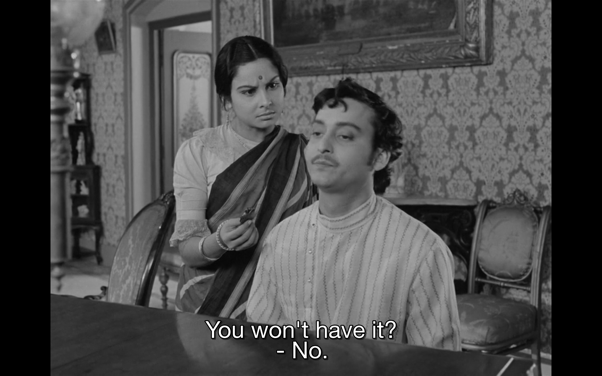

Primary Cast – Madhabi Mukherjee (as Charulata), Soumitra Chatterjee (as Amal – Charu’s Husband Boopathi’s distant cousin), Sailen Mukherjee (Charu’s Husband, Boopathi Dutta), Syamal Ghosal (Umapada – Charu’s Brother),

Music – Satyajit Ray

Cinematography – Subrata Mitra

Production Design – Bansi Chandragupta

Editing – Dulal Dutta

Shot on Film Stock, Black and White

Aspect Ratio – 1:1.33 (close to what we normally call 4:3 in Digital)

Charulata, if you see the English translation, it’s ‘The Lonely Wife’, the title of which for me means an absolute disgrace to the film. The first reason being, it completely reduces Charu’s role only being a wife of someone, which is actually the primary contradiction in the film as I understand. And second the ‘The Lonely Wife’ also sounds a bit voyeuristic. So, let’s talk about Charulata, the individual who is beyond the identities of being someone’s wife or lonely. Loneliness, anyway, isn’t an identity; it’s a phase and every one of us go through it every now and then. While some may feel as if they are in perpetual state of loneliness and melancholy, it may very well be a perception formed by others about them. That’s the feeling I initially got while watching the film. As a filmmaker and an eternal student of cinema, I shall not divulge the entire story of the film, which is just a click away on google or any web platforms. We shall critically see the elements of cinema which helped this Tagore’s story to translate onscreen and how a collective artistic collaboration led to that. ‘Charulata’ is a collective art form, at least I believe so, to respect that and the contribution of the important cast and crew of the film, it’s important to know them to appreciate the craft better.

Cinema, for many, was always a culmination of several art forms. It was never considered as a ‘fine art’ and still is called as ‘plastic art’ and ‘industrial art’. It can’t be entirely false, in fact, it makes a lot of sense considering the commercial and material nature of it. However, historically, it was also challenged at various stages. Right now, we are at that stage of history where people consider cinema complete in itself. Of course, technically, photography or theater or painting is associated with it, but the uniqueness of it can place a strong argument for us to say it’s in itself an art form, a ‘Fine Art’ form. The first sequence of Charulata, is a fine example of it. For me and many great practitioners and academicians have told this for quite some time now, cinema is more to music than painting or photography. The important factor which determines this is ‘time’, not the real time or historical time, that of course have a lot of effect on other elements, but the ‘time’ I’m speaking about is something unique to cinema. It could be the same close-up of the same actor without even a blink of an eye, but the ‘time’ with which the shot is held forms the narrative.

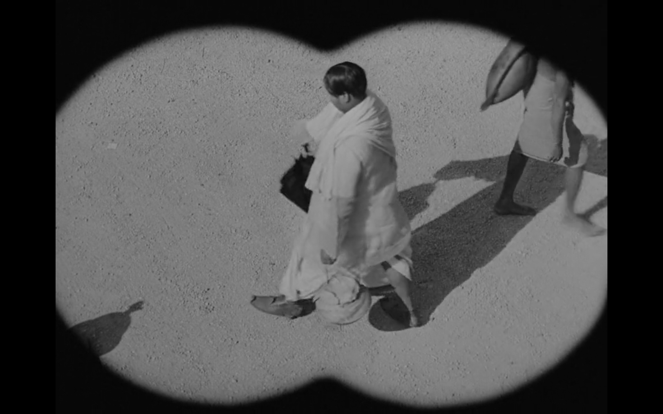

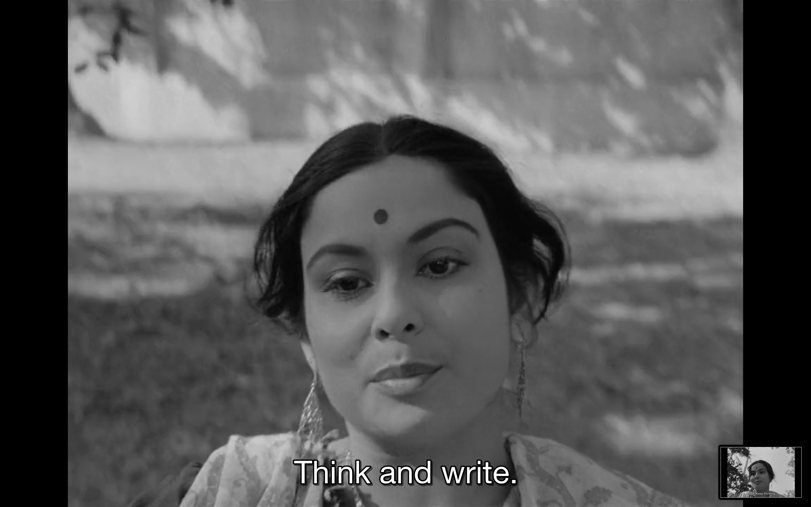

Although the first sequence has been written about by many, however, I still think it’s worth revisiting. The image of Madhabi Mukherjee with Opera Glass (or Gaussian Binoculars as its popularly called), is iconic and has always been used in posters and whenever Charulata is spoken about. The way she moves from one window to the other watching the mundane things outside the window, the smile that lights up her face, the curiosity, the binocular image, the comic depiction of some characters, the way one hears the sound of a musical instrument, sellers shouting, workers on the street, all together sets the syntax for the design and narrative of the film for us.

The title sequence which starts with the close-up of Charu working on the embroidery and the continuation till the famous binocular shot, itself establishes that it’s a Bengali Bhadralok Family from British Era of the late 19th Century. All of it is established with the careful art direction of Bansi Chandragupta with whom Satyajit Ray worked meticulously building sets to avoid any contemporary influence. And in cinema, cinematography has lot to do with art direction and mise-en-scene ( a French term originally used to mention a ‘set’ or ‘décor’ but post ‘auteur’ cinema it means all the elements inside a frame, including the properties, color, actors, angle, focal length, magnification and even the camera movement). Apart from the production design of Bansi Changdragupta, the costumes also tell us about the time, I mean, the historical time.

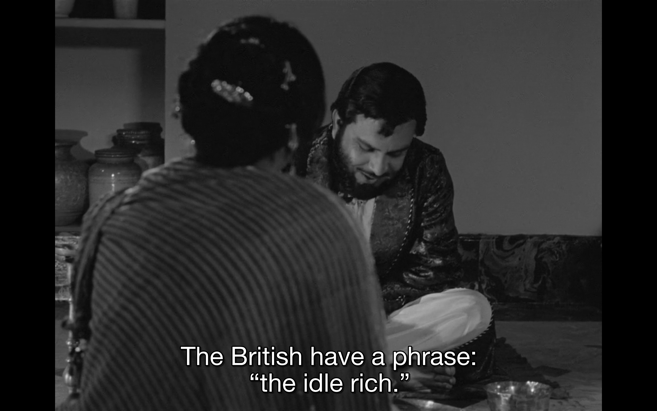

What, however, creates the real magic is the extraordinary acting by Madhabi and others and the genius of the cinematographer Subrata Mitra. After Charu’s husband leaves, the camera zooms in to Charu’s face, which then begins to express other emotions than what we have seen earlier. A sense of what can happen next. The distance between the couple is felt with very sublime gestures. With almost no proper dialogues we get to know about Charu’s soul. The character of Boopathi Dutta played by Sailen Mukherjee, also is introduced in a way for us to know that maybe he doesn’t spend enough time with Charu. Little bit about his sunk-in-work nature, with pipe and suspenders we also get to know that he comes from an educated upper class.

Books and piano have been already introduced for us to know about the interest of Charu in writing and music, which becomes very crucial in the narrative flow of the film. The point here is – how is it done? I am not a great fan of using the term ‘Visual Storytelling’ as its comes from a very flat understanding of the Cinema. Words, Images, Space, Time, Performances all are an integral part of storytelling. However, the most important and unique part of storytelling in cinema is the Montage or Edit in simple words. An image in itself has no definite meaning and serves no greater purpose, maybe for a temporary moment of compositional consumption. Only when it’s supported/juxtaposed/contradicted/preceded/joint with the other it starts communicating to us. That’s why they say Cinema Image shouldn’t be too complete or rigid, the post-modern advertisement aesthetic has spoilt our visual memory with a lot of ‘frame-filling beautification’, that isn’t necessarily a definition of a good image or cinematography. Cinema Image extends beyond the frame, it’s not a frozen narrative like a ‘Photograph’ or ‘Painting’, it definitely borrows a lot, but it isn’t just that. There has to be a space for sound, for the time to seep in, for the actors to emote and for the director to impress his subjectivity and world view; a Cinema Image should embrace it all. Otherwise, it’s just another spectacle. Satyajit Ray or any other great filmmaker in history have known this very cautiously, especially the importance of Montage and Sound.

Sound creates the atmosphere, it gives depth to the characters, voice to the director, and feelings to us. Image sound also has two major components, Space and Time. When we frame a shot, we also frame sound, we choose what we or the spectator wants to hear. For instance, when Charu and Boopathi are speaking in the night about Charu’s brother, we don’t hear much of ambient noise or any other sound; not only because it’s night, but also it’s a conscious decision to focus on the dialogue, the spoken word.

Not just in Cinema, you can try doing an experiment with yourself while reading this, if you are sitting somewhere under a fan, the noise of it or other ambient noises will be more lucid when you start reading about a fan, it is pure awareness which gives this sense. In Cinema, it’s awareness coupled with craft and practice.

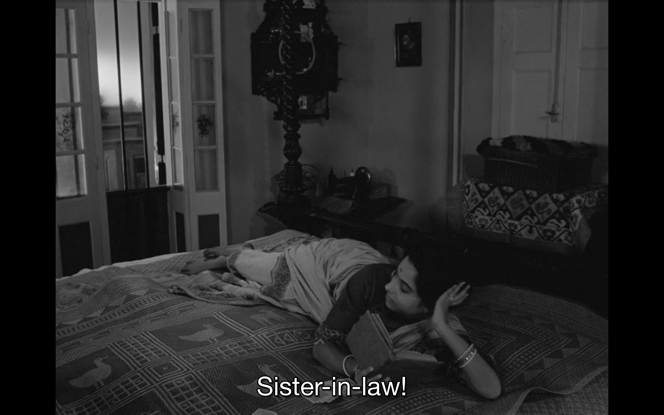

And in this entire sequence you don’t see much of Charu’s face at all. Although we can get a sense that her feelings are different and Boopathi doesn’t seem to understand it. We start to feel the sense of longing, loneliness, melancholy like her. However, we also know that Charu isn’t sad, neither does she hate her husband.

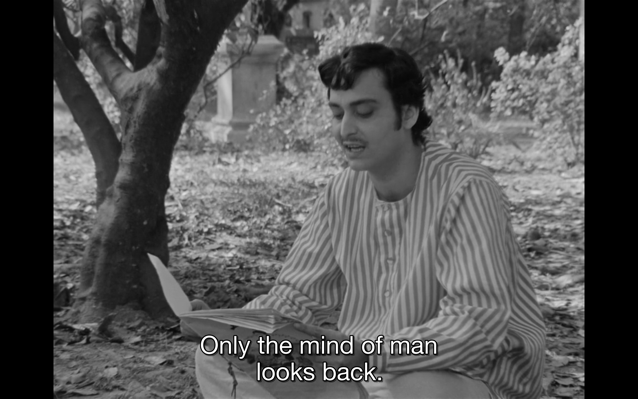

Another important aspect of Cinematic Image we can learn from Charulata is ‘Texture’ wherein a word is also a texture. Tagore’s Novel would have got a certain texture, the romantic dialogue writing of Ray with respect to the time and class he represents has a texture, and somehow the texture through Subrata’s lens seeps in the Image. Be it be the film grain or the exposure or the light or the shadow or the tracking or the zoom in and outs, the word transcends into image and vice versa. I remember one of my favourite photographers from India, Dayanita Singh, once said how Italo Calvino’s stories inspire her photographs. It’s an age-old debate between ‘Word’ and ‘Image’, which came first and what should be the base of a film. Some say it’s idea, some say it’s image, for some it’s the subject, for some it’s just a character. Biblical tales say, “In the beginning there was a word”, so not getting into the rhetoric what I propose is to use any source of inspiration for imagemaking. The impression what a word can create is multidimensional, it goes beyond the literal meaning, sometimes literary moments can give us some extraordinary clues to crack a tough moment in cinema through image. Words and Images should sometimes compliment, sometimes contradict, it’s like a love affair or a sport played, out of competition.

As the story progresses, Charu is joined by her sister-in-law Manda, who Boopathi thought would give her company, but Manda is poles apart from Charu’s interests and sensibilities. And is it just a companionship of anyone Charu needs? The question of physical intimacy, love, romance, attention, ears to listen and maybe an ultimate freedom, all of it are mixed in Charu’s feelings. It’s expressed by her gestures, with the mood set by the plasticity and clinical beauty of Victorian architecture. Charu isn’t the woman whom you will see in a typical bourgeoise melancholy dose of sitting over the window lost in thoughts, there are some moments like that, but it would it be very simplistic to brand it that way.

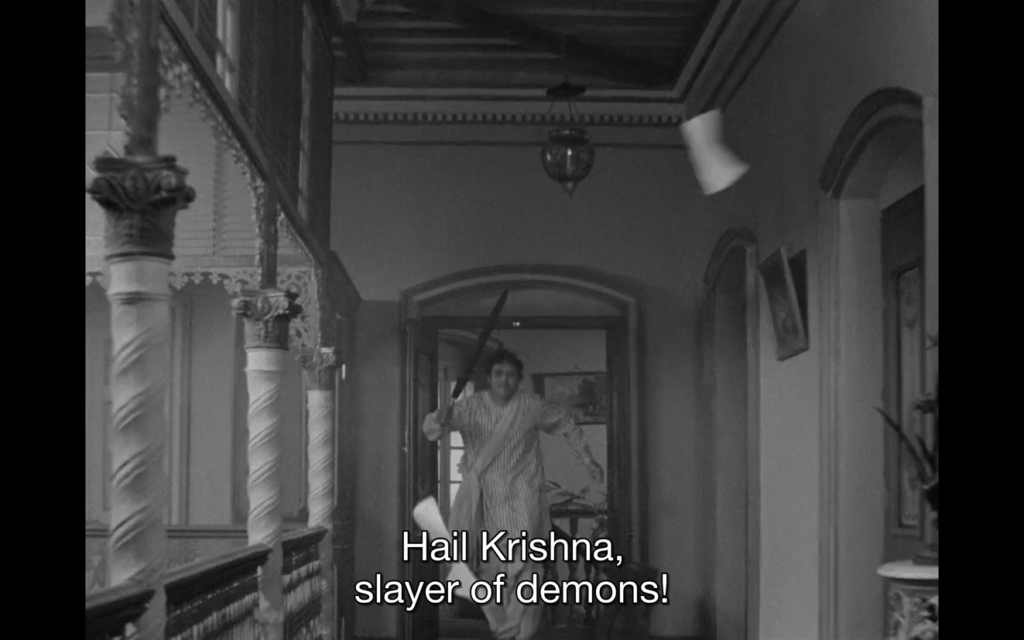

Charu’s brother Umapada joins Bhupathy’s press – this is another significant moment in the film. It’s important we see how these narrative points are shot. Be it the way the camera moves towards Charu as if it was another human being in the famous first sequence or how the sequence of Amal’s (Bhupathy’s younger cousin, also a love interest in Charu’s life) entry is designed. It’s a storm, in Charu and Bhupathy’s life, of course, but literally there is a storm like situation in the film. Although Amal is a very soft-spoken person, jovial and light-hearted (played fantastically by Soumitra Chaterjee), his entry is crafted very dramatically, plot wise it’s a shift in Charu’s life. Things do not remain the same thereafter. It’s indicated cinematically, the sound of heavy wind, clothes left to dry are flying away, doors are banging, and Amal enters almost like a God. This tells us the shift which we are going to witness hereafter. Camera becomes a tool to impress the mood and express the emotion. Optics are employed to help the narrative flow stronger. That’s were genius lies of Subrata Mitra. And it’s always a culmination. If the image stands out just for structural beauty of itself, then it means Cinema had failed.

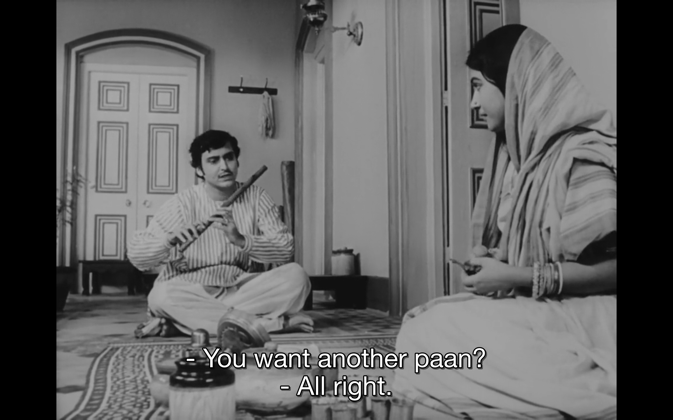

I would like to touch upon something which doesn’t have much factual evidence except for it being a trivia, but very interesting to notice and think about. It’s mentioned in a wikipedia page that Ray had problem with Madhabi Mukherjee’s Betel leaf chewing habit. As she is portrayed as an upper class woman, he wanted her teeth to not have any stains. However, he could never stop her habit. So, it’s said that Ray carefully chose the compositions and angles. There are many stories like this in cinema history, another being the one from the film ‘Apocalpyse Now’ where Copolla had to shoot majority of Marlon Brando’s portions in low-key lighting mainly to hide his obese body, but luckily it helped the character and mood of the film, and it even went on to become a style.

The reason I’m mentioning all this here is to say how a limitation can lead to something beautiful and sometimes even path breaking and historic. ‘Necessity is the mother of invention’ – my doubt is that the paan (chewing betel leaf and areca nut) becoming a very significant ‘trope’ in the film could have been due to sheer necessity to cover up Madhabi’s stained teeth and habit or it was an important symbol in Bengali Bhadralok households. In the end, it continues to be a trend and symbol which is being used in all the remakes and inspirations till date. Paan had become a narrative trope and cultural symbol.

The film had already gotten into a different zone by now; the conflicts or contradictions are established; we have also been introduced with new characters who are going to influence the narrative and Charu and Bhupathy’s life. This shift will also be visible in the visual design, if you notice carefully. As the relationship, poetry, music, and companionship grows in Charu’s life, we will notice freshness in the visuals too. This isn’t done like a formula, but it seamlessly goes along with the flow of the narrative. As I mentioned earlier, the Aspect-Ratio along with choice of lens creates magic most of the times and vice versa because the narrative gives you the scope do the magic.

Close-ups in this film are quite stunning and I don’t think they could have worked with such brilliance if not for 1:1.33 in wide

screen or scope, the space on the sides would have reduced the power and charm. But, yes, even in a wide screen ration, we have ways to do close-ups effectively; this is not to claim superiority of one ratio over the other. This is just for us to know and learn how choice of optics and technique goes in harmony with the vision and narrative of the film.

The romance builds up, Charu and Amal become very fond of each other, Umapada becomes greedy for money, Bhupathy becomes more immersed in his paper. I’m not going to analyse the entire narrative flow here; one could see it just as an introduction to see the film as a student of Cinema or as a photographer how visual elements are employed to tell a story,

impress on cultural iconism, the time, the philosophy, to open up layers, build drama and emotions and to gives us an experience. My job would be done if the reader, who will watch the film and connect to what I have written, agrees or disagrees with it or can even reject it. But the point is, to be aware and habituate oneself of watching a film from a filmmaker’s point of view.

This film is not only known for its strong narrative but also how the sequences are constructed. And many a times in film schools, individual sequences are analysed to learn the technique too. But, not to repeat myself, it all emerges from the understanding of the depth and vision and the scope. For instance, the ‘swing’ sequence in the garden is still a mysterious wonder, how was it conceived and executed. I can’t put it in words, it’s only when one sees it, one can experience the pleasure of Cinematic Image; the camera is so fluid and ambiguous yet committed to the narrative. That’s the beauty. That’s what makes it timeless and pedagogical.

It’s a poem, literally a poetic sequence, Charu and Amal are reciting poems, there is ras, there is the juice of life, and it’s designed in such a way that we tend to forget the consequence of this complicated relationship, like Charu and Amal themselves.

Days and night, the climate, the trees, the birds, the windows, the book rack, the piano, the pan, the Victorian architecture, curtains, wind everything has a significant role to play. Apart from telling the story of Charu, the film also tells us a lot about the culture of those times, the ambition of the class, men of value and men of greed, women’s role, the banality of intellectual class, the happiness of working class. Light and shadows along with the graphical compositional elements like bars of a window grill, the placement of camera, eye gaze, the way the hands and touch are composed every moment becomes significant and adds depth and layer to the narrative and the film in totality. And not to mention it’s only possible if you people carry that with its body and soul. “Human beings are the salt of the earth,” says the legendary photographer Sebastiano Salgado, for me, actors are the salt of the film.

The film leads into darkness, the tension and turbulence are so evident much that it becomes so vulnerable like a ticking bomb. But the catharsis is not expressed like in a classical drama, Ray’s brilliance is how he subverts it with the elements of Cinema and makes it more powerful but less heavy on heart. It’s painful and discomforting but also has the quality of healing. Bhupathi, Charu, Amal all are good people, they are unable to hate each other or abandon one for the other or is it the cultural constraint or patriarchal societal pressure, all of it are interwoven? It wasn’t easy and even today it isn’t easy for a woman to live a free life, or a man to be alone. There is always a choice, but only philosophically. If one had to choose between love and peace, most of us would want peace, but without love, life becomes sterile and insignificant. Without love and desire, this civilization would cease to exist. No desire means death.

Nachi Guspaithiya

Assisting in Film Industry in Direction Department and working on individual projects simultaneously.Have done Shorts and Documentaries which have been shown widely. Have been working on forming an artist collective named Potato Eaters and also have been writing occasionally on Cinema, art, literature and politics in social media platforms.