Conversation

Interview of Shahidul Alam

by Shraddha Ghatge

‘Art should comfort the disturbed and disturb the comfortable,’ so goes a popular saying. While the comforting form of art wins affection, the latter lands artists in trouble. They who ask questions, voice dissent, capture the truth through their art, words and images have rarely been any autocratic government’s favourite. These artists then have to face governments’ wrath. While some cave into the pressure, some withstand it and continue fighting the storm. Shahidul Alam, Bangladeshi photojournalist, teacher, and activist, falls into the latter category.

With a career spanning of over 40 years, Shahidul Alam has been the founder of Drik Photo Library, Pathshala South Asian -Media Institute, and the singular force behind the Chobi Mela International Photography Festival in Dhaka, Bangladesh. He was arrested in 2018 for being a vocal critic of the government’s mishandling of the Road Safety Movement protests led by the students. Following the pressure from the media and global artists to release him, he was granted bail later that year. Alam also won the Times Person of the Year (2018) and more recently, the 2020 International Press Freedom Award. Coincidentally, Samyak Drishti spoke to him on the same day (August 5), when he was arrested a couple of years ago. With an occasional sprinkling of warm-hearted anecdotes and honest answers, Alam spoke about his journey so far, his arrest and time in jail, Pathshala Institute, and the soulful art of photography. Below are the excerpts from the interview:

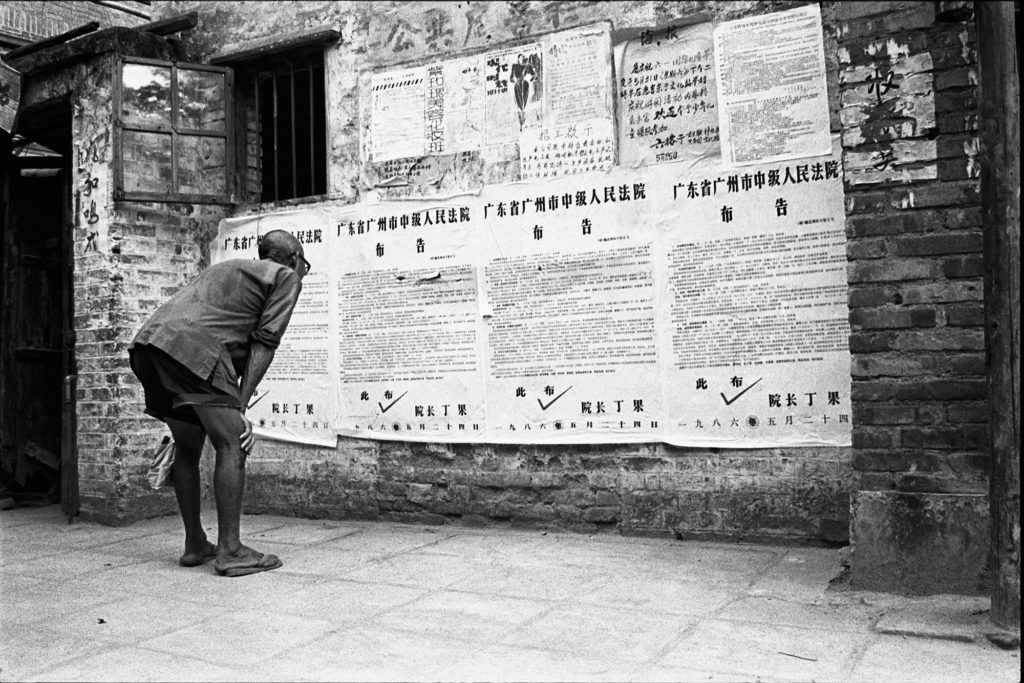

Man reading a newspaper on the wall. Photo by Shahidul Alam

You have been honoured with the 2020 International Press Freedom Award. What does freedom of press mean to you?

Shahidul Alam (SA): I see freedom of press as a disinfectant in the process of governance. It’s essential for a healthy democracy and a prerequisite for development. Intrinsically, it provides a system, which is very fluent; has checks and balances essential to ensure that the interest of the people is being pursued and not that of small vested groups. That is where a free press comes in. Not all the time, but it can work towards that.

What do you think of the Digital Security Act which is being implemented in full force in Bangladesh?

SA: It’s hugely problematic. Of course, it’s not the first one and also not the only government which has done it. There is Special Powers Act and then there is Section 57 of the Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act, 2006. When it comes to ICT Act, the new government actually said that they would replace it, improve it, and take into cognizance our concerns. But once they rose to power, they added new clauses that made it even worse for us. The number of journalists, artists, writers, whistle-blowers, dissenters were being picked up, even in the middle of the night. Of course, there is no recourse to justice and none of them get bail. It’s horrendous!

Students protesting during the Road Safety Movement in Dhaka, Bangladesh in 2018. Photo by Shahidul Alam

You were arrested in 2018 too… Tell us about that.

SA: In fact, it was this very day (Aug 5th , the day this interview was taken) in 2018 that I got picked up. The day before, on the 4th Aug , I was attacked, and my equipment was smashed up while I was on the field reporting on student protests. There were these armed hooligans beating up unarmed kids. The following day, again, I was out doing FB live feeds, I came back to do an interview with Al Jazeera news channel. I was alone in the flat that night and the doorbell rang. I looked through the window, there was a young woman with short hair who called me, ‘Uncle Shahidul’. In fact, that should have alerted me, because my students never call me ‘Uncle Shahidul’, I thought she might have been my partner’s student and I opened the door and suddenly all these people hiding outside my view stormed in.

Now, I live in Bangladesh, I know what the deal is. So, when that happened, I knew exactly what was going to happen. So, I tried to delay it as much as I could, I tried to make as much noise as I could so someone should know what’s happening to me. They dragged me down, blindfolded me, handcuffed me, and took me away. And, of course, that night I got tortured. It was a scary night. But the following morning as they were taking me to the police headquarters, I managed to see my students from the window. I knew, that if they knew where I was, they would not leave anything unturned to help me.

What do you think can be done to resolve such brutal handling of the artists?

SA: I don’t think it’s realistic to expect the governments to change, they will only change if they are made to change. In absence of that possibility, the citizens and press should be constantly resisting and monitoring the government. Even in the apparent regime, countries in South Asia – India, and Sri Lanka are heading speedily in that direction. This is difficult and dangerous. These regimes can get away with it when the dissenters and whistle-blowers are isolated and unprotected. These are brave people who resist but are not sufficiently supported. If protests take place in large enough numbers, there is no way they can withstand the obstruction.

In India, when there was this resistance to CAA (Citizenship Amendment Act) and NRC (National Register of Citizens), it spiralled out of control. Resistance of that scale has not happened in Bangladesh yet. It’s ironic, because if you consider the history of Bangladesh, many artists, journalists, activists, have resisted throughout our history. Today, people from whom you would expect to resist, the ones who have spoken out in the past, fought for justice, have now gone silent. That I think is very scary. We need to rally around with dissenters, whistle-blowers in the large numbers so that these people are not alone. It also requires responsible and creative leadership. On the other hand, even if there are a few people who could provide that leadership would lead to dramatic shifts.

Shahidul Alam with a Rohingya child. Photo by Md. Shahnewaz Khan

Do you think the line between journalism and activism are blurring these days?

SA: I practise journalism because it is such a powerful mechanism to engage and resist. And I use Art because, again, it gets under the skin. You can do things that are very difficult through journalism and art. It’s a very powerful combination. I myself, am an activist, an artist and journalist, and I see no confusion there. The confusion comes in when within our practise we forget those differences. As a journalist, I need to adhere to the rigours of journalism, I need to be fair. I won’t say objective because it assumes that we don’t have a position; of course, we all have certain positions. I wear my politics on my sleeve and have made no pretences about being anything else. If there was a fence and there was a powerful and an underdog on either sides, I wouldn’t stand on the fence. I would clearly be on the side of the underdog and that is my position. Once you have made that position clear, as an artist, you use the power of art, to do what you can. As a journalist, you adhere to the rigour of the profession. I think we are not mutually exclusive.

Tell us about Drik Photo library and Pathshala Media Institute

SA: The photo library began in 1989 and at that time there weren’t photo libraries in our part of the world. I’m fond of an African expression – ‘Until the lion will find its storyteller, stories about hunting will always glorify the hunter.’ And I followed that. Our stories have been told by and large by white-western photographers, they have parachuted in, usually had diarrhoea for the first couple of days, taken pictures on the next, and gone back with pretty much the stock images they aim to get. They were hunter-gatherers; they were not interested in the nuance stories that needed to be told. Some of what they were telling about my country is that we have poverty, we have strife, we have disasters that we cope with. But that is not certainly our only identity. I think the real story is the resilience of the people, their capabilities to withstand such enormous pressures that deal with in their day-to-day lives by helping one another.