Sept 2020 Vol 01 | Issue 02

KOLKATA: The Darkness of

Social, Real and Life Narratives

Prof. Y. S. Alone

All the photographers are from Kolkata, a city of maximum, and the city known for its passionate art lovers. The state of West Bengal is also known for its left dominated politics which has always stayed away from any transformation politics and caste and communities discrimination. It never addressed the issue of social change; instead, it preferred to sleep into mere power politics like any other state in India to keep people under the perennial syndrome of ‘protected ignorance’. The city has its own life and the photographers have attempted to come out to capture the dark, the social, and the life narrative.

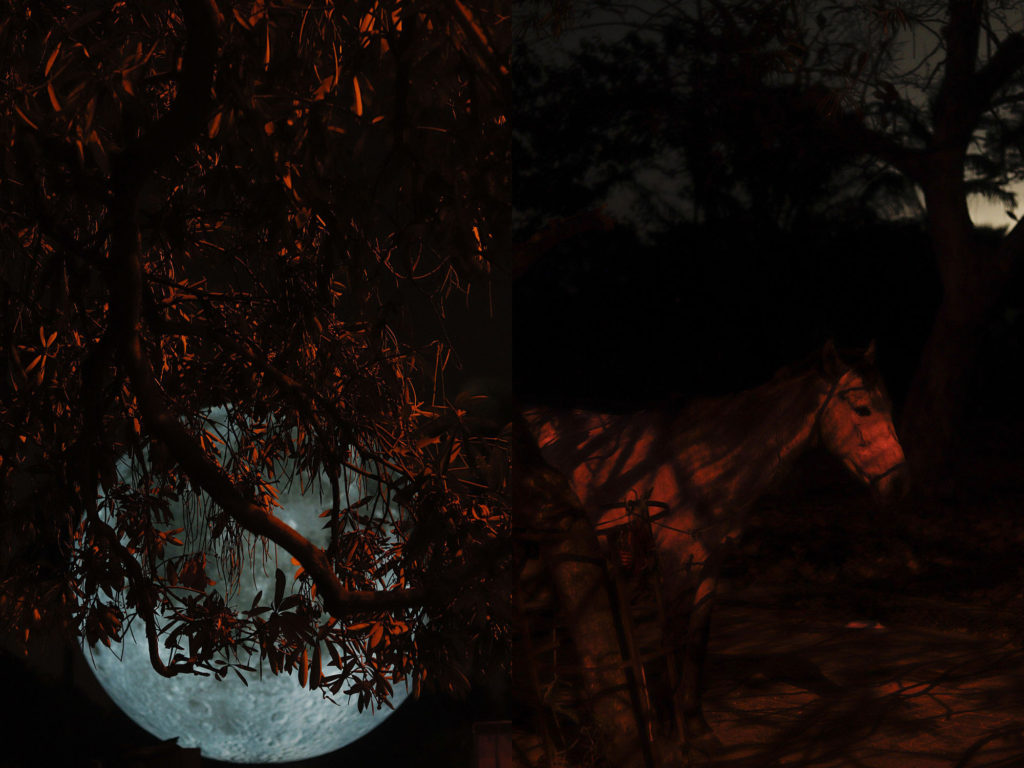

Aniruddha Sarkar wanted to be a football player and his accident debarred him forever from the football. He turned to photography as a part of his passion to explore objects abandoned in darkness and mainly different means of transports. The focus of attention in his images is to capture objects in its centrality of the frame with a spotlight, which is not constructed while clicking the images. Transport vehicles are the most important machine objects human has produced for its utility that revolutionized the travel in nineteenth and twentieth century. In the days of new environmental regulations of the Government of India, the vehicles have their licensed-life and depend on its permit regulator. Thus, they fade away from the roads in a periodical manner and become a junk either in the backyard or the garages or the different workshops of the junks. Such junks are an out come of industrial waste. Aniruddha attempts to capture the abandoned objects mainly in the nights as to how they are seen. Vehicles are seen engulfed and surrounded by vegetation that is seen during the monsoon or the non-summer months. Little illumination on the object brings back the heaviness of the object. In the urban landscape, there are a great number of cars whereas the semi-urban and rural will see the junk of two wheelers and the tractors, and the rarely the agricultural equipment/machine. On the other hand, there is also the government junkyard of railways capturing the aged out of service coaches. Service is associated with every object as it served its purpose, after which, it becomes a lifeless object waiting for its attention. Aniruddha captures the vehicles before they are completely eliminated, before its dismantling process.

Extreme darkness and little light is a deliberateness that goes with every frame and at times, the objects identity is completely blurred beyond its identification and becomes an abstract frame.

Dipanwita Saha is a software engineer by education and has moved to photography. Her father migrated to Kolkata in 1971 as a refugee. Her growth as a displaced refugee and struggling to be part of the erstwhile nation is a tell of a difference and has influenced her practice of photography. Historical, cultural and political narratives are her subjects of explorations and interest. Photographing her own diary is an act of revisiting the past memories all the time and recreating it through photo-collage is to reassert the fact that the memory though is documented, but its conversion into the photo image is a political one. She claims

to be interested in documenting the human life and its historical characters. The pandemic has its impact on her thinking about the image and the human behavior. Her family images are aimed at larger social self as a unit to constantly remind the trauma of refuge the family faced. Starting by Yashica camera, Dipanwita has moved to explore images of memory. She experiments with multiple color tones in the images, having color monochrome, images of humans, family and landscapes. Her landscapic images stand between her romantic admiration and realities of momentariness. When it comes to human images, she documents them as posing pictures as well as images of uncertainties. There is no fixity in her technical sophistication. She uses rawness to make the image expressive as part of her politicality, at times images almost getting into the mold of early Bengal modernist expressionistic images.

Swastik Pal is a young photographer studied mass communication in Kolkata. He documents life of his own uncle ‘Tukka’. Being close to the subject of image, Swastik moves everywhere with his subject. Though he is photographing an individual, but the social is necked and real in his images. Poverty and conditionality is not romanticized. Being part of the same ethos, his commitment to the self is the strength in many ways, which he adds to his practice. Worsening of health is a deep cause of concern that gets captured in the images of Tukka. He being a witness to the life of his uncle, observed changed behavior of his own family and their changing attitude. When Swastik takes his uncle to the nearby water tank, his outing is a memory of past. Being ill all the time, it becomes difficult to go out. By revisiting the same place again after a prolonged gap, Swastik’s uncle has a feel of location and making his own explorations becomes important means of expressions. At home, kite making is the passion of Tukka with basic raw material. It’s a chronicle of the Tukka via the agency of Swastik. Swastik’s camera lens moves from interior of domestic space to exterior of the location itself. While interior is a real strength for him, the exterior is marred with problems of the different nature of conditionality where the image is build to capture the thick condition of the real existence. Interior space is a home space where Tukka stays alone, image though is simple, but it has strength of a

human narrative like an autobiography, it’s a quest to document a life of an ordinary.

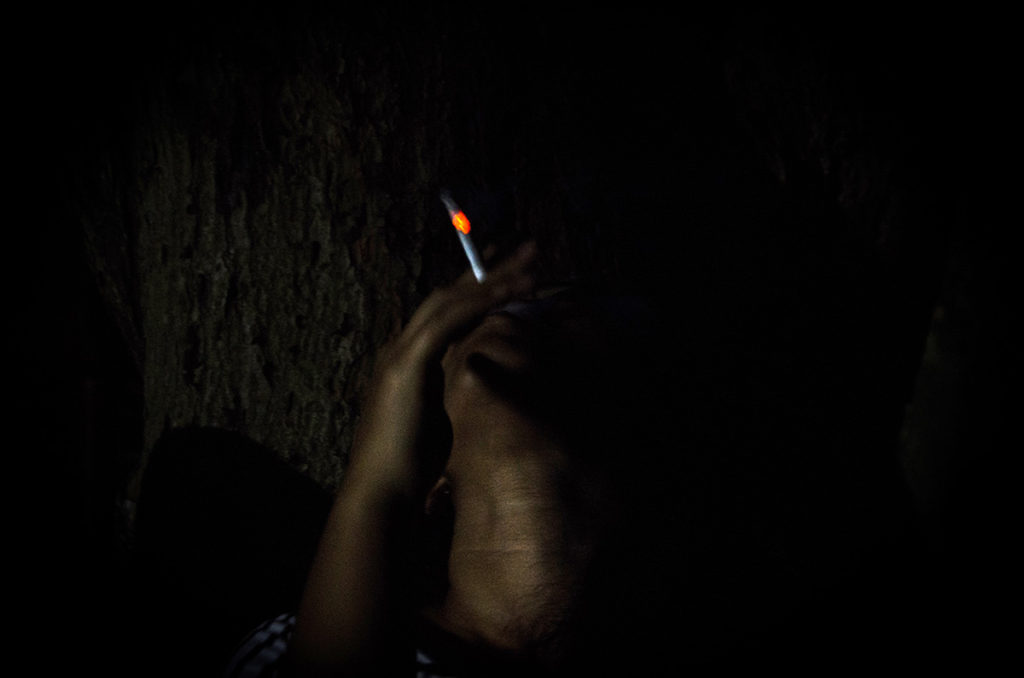

Labor migration, industrialization, hired labor are all though part of the modern economic system but it has its roots in the traditional caste system. With the collapse of the cotton mills in eastern and western India, situation made a drastic change. Mill workers lost their livelihood, small-scale industries suffered but labor migration did not alter at all. Jeet Sengupta sets out to explore the life in the darkness. He finds no streetlights in some of the areas in Kolkata despite the fact that it is a metro city and a city of maximum. He encounters the most indispensable labour class in the city of Kolkata in the night hours. They are

soldiers of night patrolling and guarding the areas. They are popularly known as ‘Choukidars’. He observes a strange relationship of this community with the police and people in the area. Essentially being part of darkness, Jeet captures the locations of the so-called ‘haunting’. They form strange places in the darkness where no body wants to go, but for these guards, there is a compulsion to scan such areas, which they do collectively. Without any proper training, they setout with the stick, a dry battery torch and a whistle tied to a thread in the neck to protect the areas in the dark. Some wear shoes, some with simple socks and a chappal. It’s a strange ways of doing things in India. Each image is a portrait of the individual guard, many times as posing pictures. All are captured in the streetlight. Some places that are considered to be ‘hauntings’ are interesting images that attempts to document the status as has been thought by the human consciousness of ignorance all the time. These local guards have become part of urban life, working on collective contribution by the residents, a support system that is part of informal economics and labor system.

As stated earlier, the state of West Bengal has been the hot bed of left politics imagined revolution without addressing the structured problems associated in the social sphere. The imagined revolution has no space for rejection of the blind belief system. Their chronicle is that of rejection of the constitutional democracy and establishes a state without changing the consciousness of the people. It may also be observed that the claimed Naxal movements in India has not brought any change among the tribal and rural masses, neither there is any sensitivity for health care and education nor any agenda of social change, In the urban areas, being Naxal becomes an act of heroism without critical evaluation of the self and projected as the alternative. Consciousness of the public is rooted in the ‘protected ignorance’ that does not get addressed in any claimed radical ideologies. Their ideological shift to violence is to justify their own self rather than bringing any transformations in the society. Caste-Hinduness is an integral part and such movements have not brought any transformations as such. The only positive of these movements is to air grievances of the agrarian communities and the total reject of the feudal lords. As Dr. Brahma Prakash, a faculty in the School of Arts and Aesthetics says ‘only feudal will admire and love the rural’. In this context Ratul Chaudhury’s photographic images tries to retrieve the past of the violence that was consciously chosen category. He documented the incidents of eradication of the activists by violent means. His critical lens documents the unpleasant incidents of violence where democratic claims become very difficult. His critical take to document those who have been part of erased history and bringing back the memory of their existent as another set of citizens who differed from the state. The state failed to address their issues. Condensed milk cans, nails, threads etc. were recovered by the state police that have become object of the preserved memory. Ratul makes a diary of the objects and dig the archive through newspapers. His images are also records of brutality not directly shown but by presenting the images of victims as representative figures. The 1971 state violence is a brute memory that killed many youngsters by police brutality. The police have no right to kill its citizens but periodically the police administration gets involved in killings under the pretext of law and order and by declaring its citizens as ‘hunted’. Violence cannot be justified neither by the state nor by citizens. Ratul’s images are repository of the violence that emerged by all unconstitutional means. The youths attracted to such ideological streams do not realize to change or throw away the caste-

structure of the Indian society.

Nilargha Chatterjee is a self-taught photographer; his basic education is in the field of mechanical engineering. Nilargha ventures outside the Kolkata city to explore his photo images and in the process, captures life of Santals who are a tribe in the state of West Bengal. Ramkinkar happened to be the earliest one who brought Santal life as part of his thematic in art practices. Nilargha understood the problem associated with the tribe and their historical oppression. In todays’ democratic world they are devoid of basic human rights, health care and education. According to him, the community is also exploited by the Christian missionaries and their life is reduced to the cheap labor. Their living condition has not changed. His documentary approach is not to romanticize the rural but to unfold the pain and severe hard life the community face in their every walk of life. Their thin body is a testimony to the fact that the tuberculosis is rampantly present as community disease and there is no way on the part of the state to change their life. Dignified life has never been part of the left, right, center politics in India. Their laborious life as farming community involves self-labor and has to survive accordingly. For Nilargha, exploration of paddy field is not captured as high village romanticism but to denote a life of hard labor and life where community markers are rampantly present. Like other Bengali communities, Santals also live near the water bodies and live an ordinary life but they do face social discrimination. The class syndrome of the Bhadralok construction of the Bengali intellectuals have been responsible for further segregations and impose their own self on the rest of the subjects in the state as well as outside.

In India, there are only three states that are passionate about football, West Bengal, Kerala and Goa. Football passion of the Bengalis is phenomenal and has gripped the urban and rural Bengal considerably. Their life revolves around all the football legends and has taken the game as part of their cultural matrix, no matter how many stadiums are really equipped with world-class football turfs and amenities. Their football grows in the field and everywhere is of great passion in the state of West Bengal. Paromita Chatterjee is a documentary photographer based in Kolkata but ventures out of Kolkata to document a life on the football and mainly the female youngsters. Promita shows natural affinity to the subject of gender body and environmental concerns. Girls from various strata of the Indian society play football on the civic and school grounds. The girls

covering their heads reveal their community identity and there is no common code arrived at to follow in the game. There is a liberty to adhere to certain customary practices of the person. The civic play ground in the urban areas are full of girls playing foot ball with shoes and long socks whereas some practice in a normal salvar-kameez attire. Their choice of cloths shows their affordability to have or have not the proper dress and shoes. Shoes are very important in the game but some play bare foot showing their passion for the game. At times images are posing one but they do narrate their stories to tell the viewers that they have arrived and will survive for a long. Bare foot football is a difficult task and girls are willing to take a risk to enter on the ground bare foot to show their resolve for the game.

Disclaimer

The opinions of the author expressed in this article are his personal. They do not reflect the opinions or views of those of Samyak Drishti or its team.

Prof. Y. S. Alone

School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University New Delhi.Presently he is working at School of Arts and Aesthetics, Jawaharlal Nehru University, New Delhi from 8 th March 2007 onwards. Previously he worked at Dept. of Archaeology, Deccan College Post Graduate Research Institute (deemed university) Pune and at Dept of Fine Arts Kurukshetra University, Kurukshetra.